From Philip Eoute, Beckenhorst president: During this Christmastide season, I’m reminded that people often use this time to reflect on the past as they plan the year to come. December 2025 marks 25 years since Dan Forrest received his first acceptance letter from Beckenhorst Press. Then he was an aspiring composer; now of course he’s firmly established in both the concert and church choral worlds, and he serves at Beckenhorst as vice president and editor.

To mark this anniversary, I recently sat down with Dan and interviewed him on his journey over the past quarter century.

PE: Tell us about where you were in your professional and compositional journey back in December 2000, when Craig Courtney accepted your first piece at Beckenhorst.

DF: It’s wild to think back to that time! So much has happened. I’d just graduated with my undergraduate degree in piano performance and was about to start my master’s degree, also in piano performance, and with a teaching assistantship in (you guessed it) piano. I was still hoping to conquer the world on my piano bench, and was just starting to consider teaching piano at the university level.

My choral aspirations were just beginning then, influenced by hearing excellent collegiate choirs for the first time and discovering CDs from the Cambridge Singers. Morten Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium was still relatively new then as well. These influences led me to write more for choirs and the voice, not just for piano.

At the time I had collected several rejection letters from a handful of publishers, but my only publication was a single vocal solo in a collection from a small local publisher.

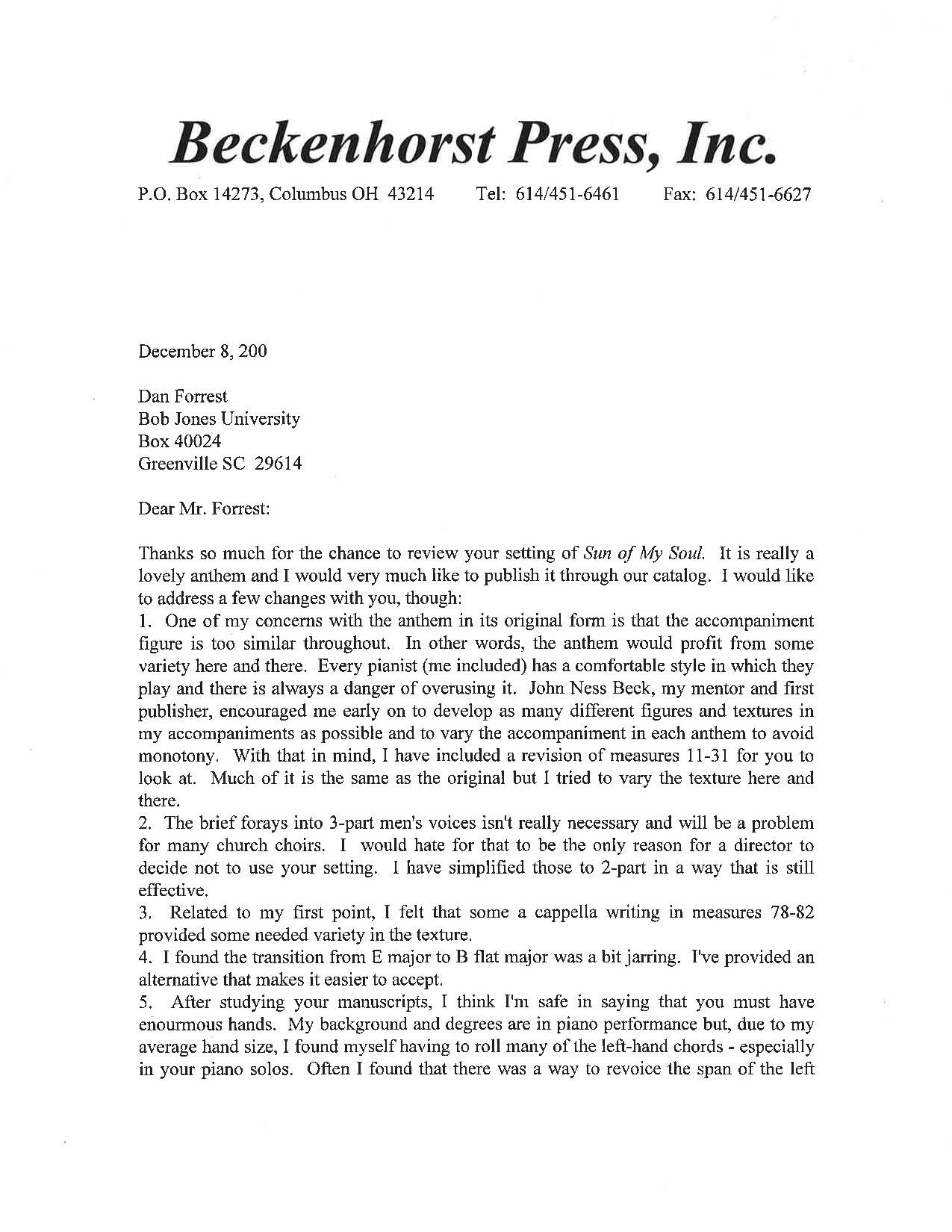

PE: We dug up your original submission letter for Sun of My Soul [BP1605] from early 2000. Do you remember mailing that envelope? What was going through your mind as an aspiring composer sending your work out into the void?

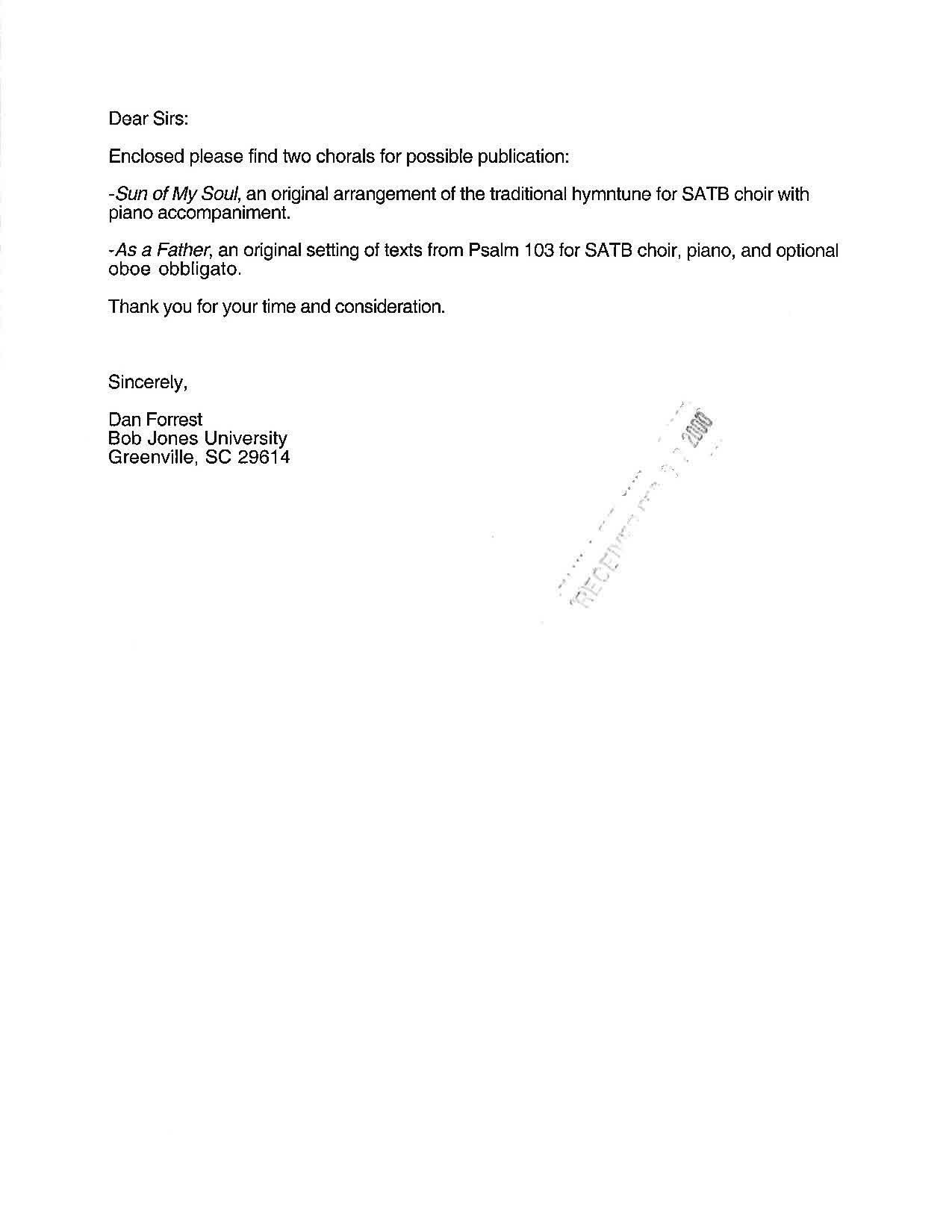

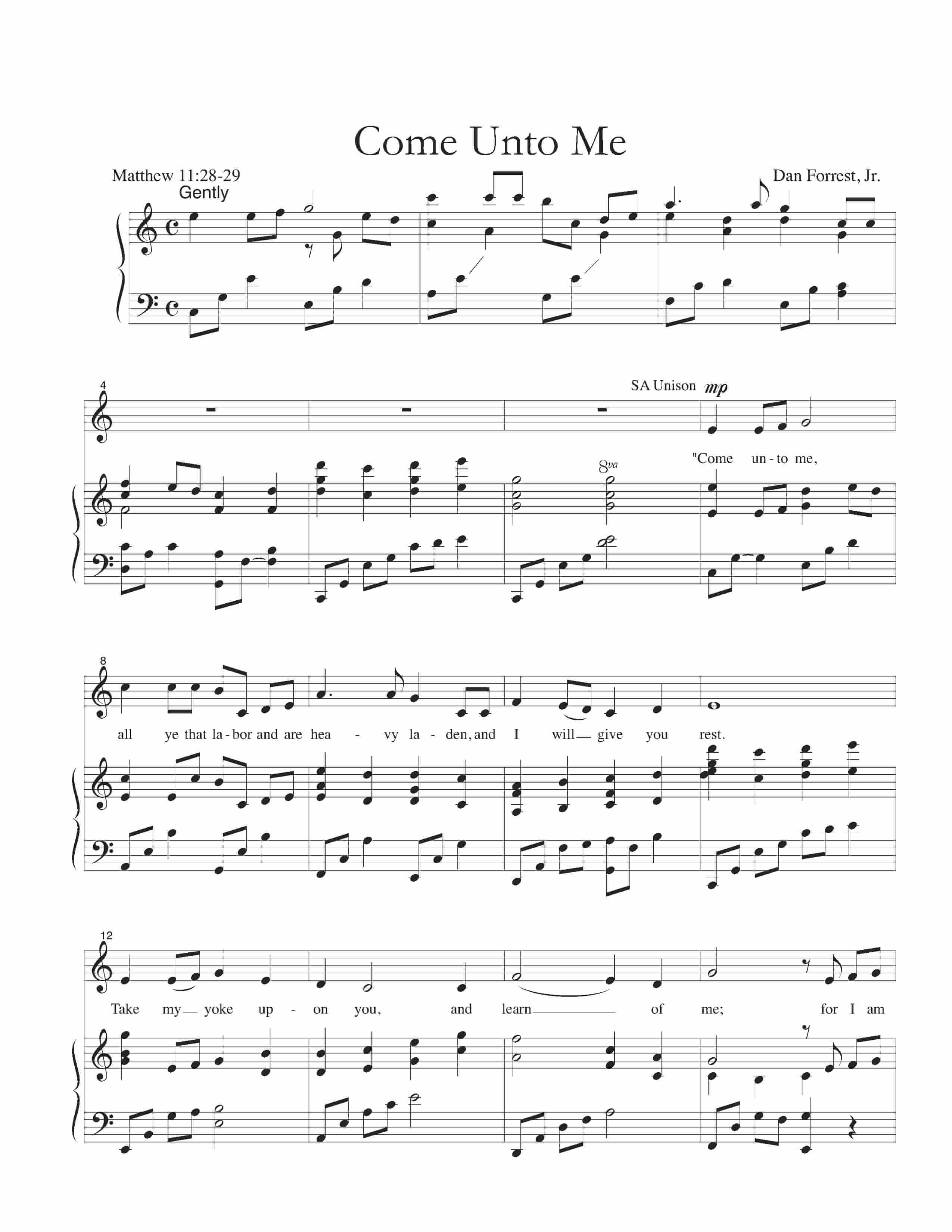

DF: Ha, well, it wasn’t quite “the void”. I had already submitted several pieces to Beckenhorst but none of those had been accepted. And I sent those pieces to several other publishers, too, once Craig rejected them. I had a big stack of rejection letters I collected! My first submission to Craig was Come Unto Me a year or two before, and even though he rejected it, he wrote encouraging things about my work and asked to see more of what I was writing.

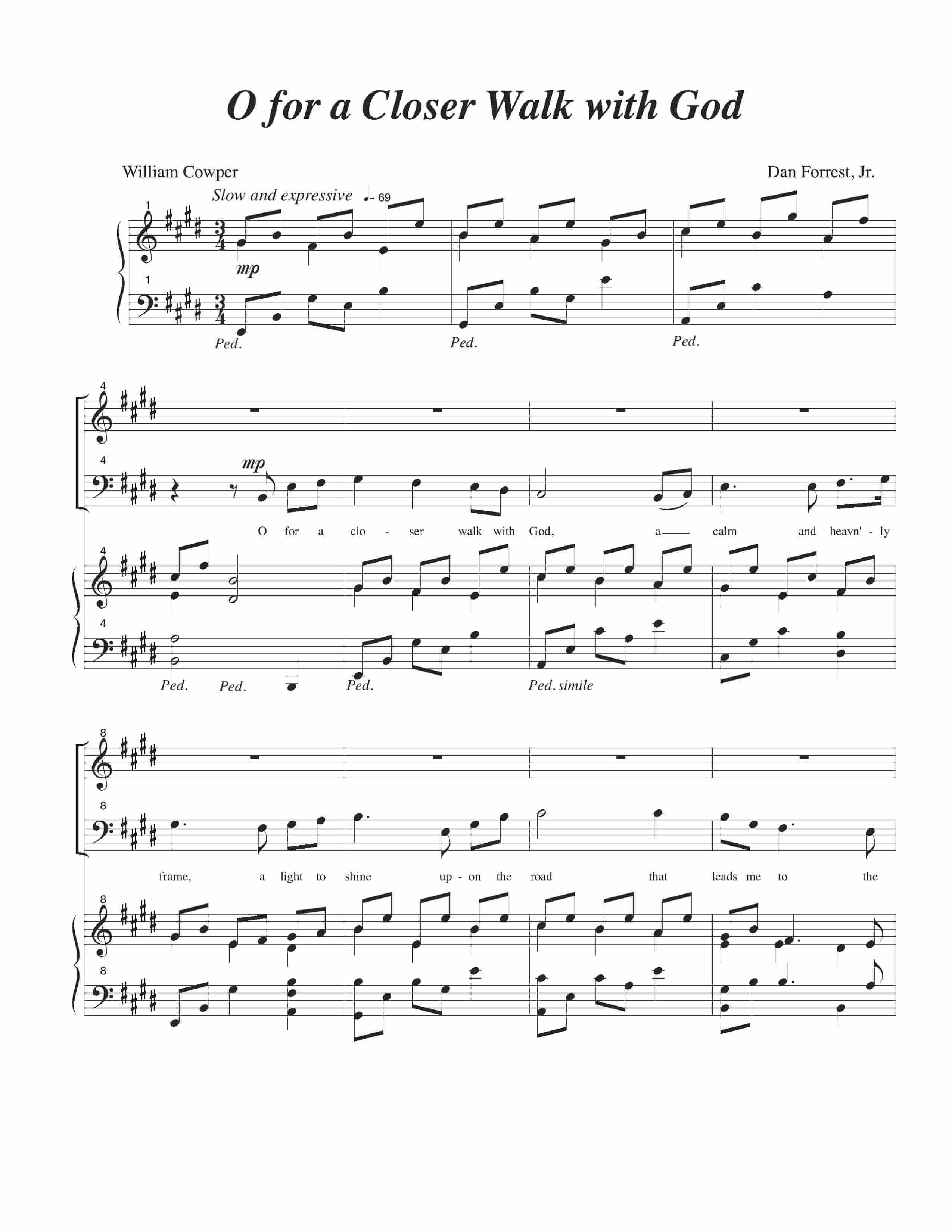

I sent him a few other pieces along the way, including O For a Closer Walk with God and O Love Divine. None of these early submissions got published (and I would reject them today, too), but I still have those files.

Back then, Craig was kind of a legend in my mind. Beckenhorst published so much great choral music that we used at school and at church, and there were so many pieces in their catalog that I admired or even revered, for both their creative idea and their craft. When I sent Craig a submission, I felt like Oliver Twist approaching the headmaster’s table to ask for more!

If you look at that original submission letter, you’ll see there was a second submission included, As a Father. Back then, I thought that Psalm setting was the more likely to be published—I thought it was more artistic, perhaps more “worthy,” whereas Sun of My Soul was a fervent but less-familiar text set to a tune that most of the Beckenhorst market already knew.

PE: I want to talk more about Sun of My Soul. What drew you to the text and tune?

Sure. It wasn’t widely sung in the circles I came up in, but the church I was attending at the time sang that hymn congregationally in evening services as almost a Vespers feel at the close of the day. So it was both unfamiliar and fresh, and I loved the text and the tune. I kept hearing more creative textures and harmonizations than the hymnal provided, so I eventually started writing those down.

It took me a really long time: I agonized over every bar, sometimes spending 30 minutes in a practice room trying to find the perfect accompaniment or countermelody for just one four-bar phrase! But eventually it all came together.

Craig had his list of changes, of course, which were all wise. I remember feeling like it was such a momentous thing to be making those changes and hoping he’d be pleased with the new version. (Spoiler alert: he was, and this ability to hone my works into better versions of themselves eventually led him to offer me a job alongside him in 2011. Craig always has said, the first step to being a good editor is being able to self-edit your own work!)

PE: Is there anything in the anthem that 2026 Dan Forrest would write differently than 2000 Dan did?

DF: Oh, absolutely. It is such an early piece, and I see so much that I still needed to learn. I think the underlying motif and counterpoint are strong—I’m glad to see that I was thinking that linearly even by the end of undergrad!

But the large reaches aren’t ideal, and I’m glad Craig addressed that. Today I’d probably seek a little more interesting accompaniment in places, and I’d avoid (or at least improve) the half-step modulation. But some of that is just time and style and taste changing, too: this worked better in 2000 than it would today.

I also want to say one more thing, especially to today’s aspiring composers: Looking back at this piece, I’m not sure if I would have accepted it—but I’m certainly glad Craig did! And I always bear this in mind when I’m reviewing submissions now. Craig gave me a shot even when my work had a long way to go because he saw future potential. So I’m always looking for that kind of future potential in submissions.

PE: In some of your early correspondence, you mentioned submitting work at the suggestion of your mentor, Joan Pinkston. How important was that encouragement for you at the start, and how has your view on mentorship changed now that you are the one mentoring new composers?

DF: Joan was my first composition teacher, and she made an invaluable and indelible impact on me as a musician and composer, in both her theory classes and our private lessons, as well as through her example as a professional composer. She’s one of several people I list in my public bio as key musical mentors and influences. She and I worked hard on both the pieces I submitted and even the wording of the cover letters! She suggested including her in the cover letter so Craig would know I had her stamp of approval.

At the time, Joan had several pieces published through Beckenhorst’s BMI imprint, High Street, and was still actively composing and submitting new work. She’d traveled the path and found the key to get through the door, so I was more than happy to get her input and her introduction to Craig.

These days, people are much more interconnected (readers wouldn’t have ever seen this interview back then!), but back then, it felt significant to have a personal endorsement like hers. Endorsements aren’t as big of a deal today, but mentorship has always been—and will always be—critical. That’s why I try to invest in new composers as they submit worthwhile but not-quite-ready-for-press anthems and arrangements. It’s also the impetus behind my work with the John Ness Beck Foundation Composer’s Workshops over the past decade and a new initiative starting this year, Forrest Fellows.

PE: I’m glad you mentioned Forrest Fellows. Can you tell readers more about it?

DF: Forrest Fellows is my new composer mentoring program. It sort of replaces my work with the John Ness Beck Workshop, as well as the private lessons that I’ve taught on and off for the last 15 years. It’s a small-group experience—bigger than private lessons, but smaller than the workshops I’ve run—so that we can really dig deep into each composer’s work and give very detailed input into their voice and path; but the small group setting allows me to teach in a way that benefits several people at once. I think it’s the balance of effectiveness and efficiency that I’ve been looking for, and ironically it’s pretty similar to Alice Parker’s Melodious Accord Workshops that influenced me deeply over the years.

Best of all, the John Ness Beck Foundation is supporting every accepted composer with a scholarship that’s around 40% of the fee to attend. It’s a great setup and I’m so excited about it. The first cohort will meet in September, and applications are open now under the Forrest Fellows tab on my website.

PE: Thinking about your journey as a composer, it’s an understatement to say that you’ve come a long way since that first publication! As you look back, what do you see as the major turning points in your career where you see notable advances, whether in compositional voice, reach, success, or a mix of all?

DF: It really is hard to fathom the journey. 2000 Dan was over the moon to get a single piece accepted at Beckenhorst, and now, somehow, I steer this ship!

This first publication was of course a key turning point, but several doors opened, especially in the concert choral world, during my doctoral work. Around 2005, I received the ACDA Raymond Brock Student Award for “Selah”, and the ASCAP Morton Gould Young Composers’ Award for other movements of Words From Paradise. I got to meet Philip Glass, Peter Schickele, and Cia Toscanini at the awards ceremony at the Lincoln Center! Also, Hinshaw accepted Words from Paradise and A Basque Lullaby for publication – those were my first concert works in print, back in the day when Hinshaw was publishing Rutter. I couldn’t believe it!

I studied with James Barnes during my doctoral work, and his extraordinary skill in instrumental scoring and just innate musical sense added so much to my palette. His ability to apply examples from across the repertoire to his students’ work was such a gift. His mentorship in these areas combined with earlier training in piano and choral composing perfectly, enabling me to write successful, meaningful choral-orchestral works.

2012 was another milestone as I retired from university teaching and set out to compose fulltime. I remember turning in my office key on the first Saturday of May, then starting composing my Requiem for the Living two days later on Monday morning. I was thrilled to have a major commission and premiere for the Requiem and just tried to write the best piece I could for that first performance. I never could have imagined how far it would go, but it went on to be my “breakout” piece, and remains my most widely known major work. It’s probably fair to say that the Requiem launched the rest of my concert music career.

As a composer, I think I see my journey as one of always seeking a great musical idea, but then continually raising the bar for what I consider to be a great idea. I’m less and less easily pleased, and I’m endlessly looking for ideas that feel truly great. Yet I do see moments in my first decade of composing that really have great ideas: the simple elegance of Lord of the Small or Good Night Dear Heart, or the simple shining motif and soundworld of The First Noel, or the expressions of music and text in the Requiem. So it’s an endless search for the next great idea, but it’s not always linear progress. It’s more like constant exploration of any nook or cranny in a big open space that might have something worth keeping.

PE: The choral publishing industry has changed significantly since you were a new composer. What are the most notable changes you've seen over the last 25 years?

DF: Certainly the church choral market has changed. Overall numbers are smaller, and I think pieces have to stand out from the crowd much more in order to sell.

Styles change, too. Some things that sold like crazy in the early 2000s just don’t connect in the same way today.

For artists who try to create great (but marketable) work, there’s always this tension between honesty/integrity and “what the market wants”—specifically the subset of the market you’re aiming for. For artists, if you’re not careful, you can easily pigeonhole yourself into a small corner of the market (or even just whatever pleases you), or you can become so market-driven that you lose your voice (and maybe your love for the craft). It’s a constant balancing and calibration process, but instead of just giving in one way or the other, I encourage composers to look for where those areas (market concerns and your voice) overlap.

At my best, I hope I write music that expresses my own thoughts and values and voice, speaking with integrity and artistic honesty, and yet also find at least a certain subset of the choirs of the world that want to perform that kind of music. And this is the kind of work Beckenhorst seeks to publish as well, capturing unique voices across the landscape, not just one “Beckenhorst voice.”

At various times I’ve been tempted to go too far in either direction. My academic training looks down on “pandering to the market” while my business and publishing experience are always highly concerned with marketability. Craig was concerned when I told him I was going to do a doctorate, that it would ruin me for usable choral music—and I understand his concern! When I’m wearing my BP Editor hat, I do have to think about staying in business, of course; but for both myself and the composers I edit and mentor, I’m always trying to find the sweet spot in the Venn diagram where we can “have it both ways.”

PE: What opportunities excite you as you look to Beckenhorst’s next 5 to 10 years?

DF: Yes! First of all, our concert music presence continues to grow. Beckenhorst has historically operated at the intersection of higher art and functionality/accessibility, which means our publications are often performed in both sacred contexts as well as concert contexts. We’ve leaned into that even more in recent years. The composers who we publish often write concert works, not just sacred ones, and I hated telling them “sorry, this is a concert work, we only want your sacred works.” That dichotomy contradicted everything we’re about! So I’m excited to bring my concert music experience to Beckenhorst. Our Concert Series publishes pieces within the Beckenhorst ethos written for concert and school use. We’ve already seen some really great successes with our concert publications, and they continue to grow every year!

Beckenhorst has also recently launched live concerts, where the Beckenhorst Singers take their talents from the recording studio straight to some of Indianapolis’s finest sacred spaces. Our inaugural concert was held this past August, and it was so satisfying to be making live music at such a high level for a live audience—people absolutely loved it. Tickets are on sale for our next concert Sunday, February 8, 2026.

For myself, well, I have a couple of things coming up in the next year or two that are really exciting for me, but I can’t quite share them publicly yet—you’ll have to wait and see!

PE: One more question, this one a little more lighthearted: It’s fun to see Craig’s critique of your “big-handed” writing many years ago. I know you’ve adapted some, but even still some pianists find your reaches and leaps just a bit…stretching. What advice do you have for composers and pianists?

DF: Ha, OK ok, yes. Oh, I’ve changed, believe it or not! Look at my earliest piano collections like Prepare Him Room or My Father’s World, and you’ll see how I used to write. I needed to get rid of that kind of unnecessary difficulty. Still, I reach a 10th easily, and any pianist who does, uses it widely in their playing and improvising— something like C-G-E in the left hand is just such a nice, sonorous, resonant sound. In my writing I do try to restrain that for the majority of pianists, but I keep a few larger chords here and there because the extra resonance is worth the musical effect, for those who can reach. I always encourage pianists to roll those chords if needed—that's just part of normal pianistic practice. I mark rolls where I want them for expressive or dramatic effect, but even where I haven't marked them, I understand some hands can't reach as far, and I always presume they'll roll those chords.

Another little trick is, when I write a three-note chord that spans a 10th, you can often omit the top note if needed (and maybe even add that pitch into the right hand in whatever octave it's currently playing). Doing this often leaves a fifth or sixth in the LH, which provides more richness than just an open octave. This method can be handy in places where a roll isn't workable, or lacks solidity or strength.

Sometimes I cue-size the top note to encourage this kind of thing, but even when I don't, dropping that top note can be a good solution for smaller hands!

In the end, writing challenging yet accessible accompaniments is a way of influencing the market rather than just following it. I don’t ever want to frustrate musicians, but it’s not a bad thing to give musicians a challenge—many musicians thrive on them, in fact.

PE: Thanks for sharing your thoughts with us today. Here’s to another 25 years!

US Dollar

US Dollar